|

IN THE STUDIO

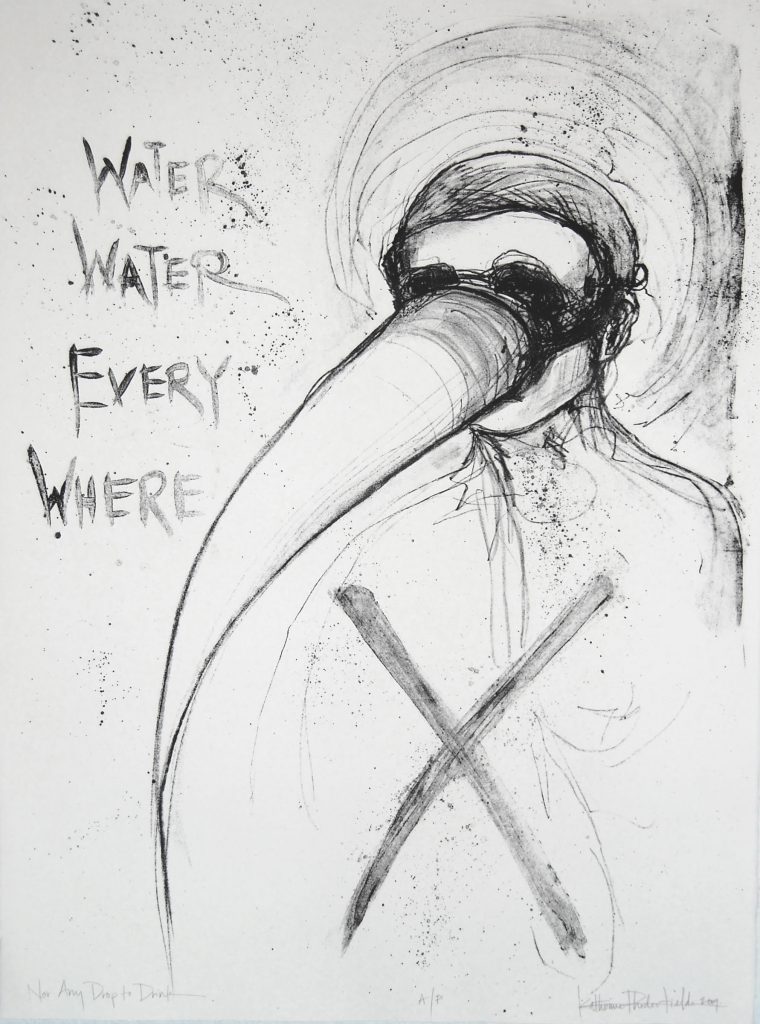

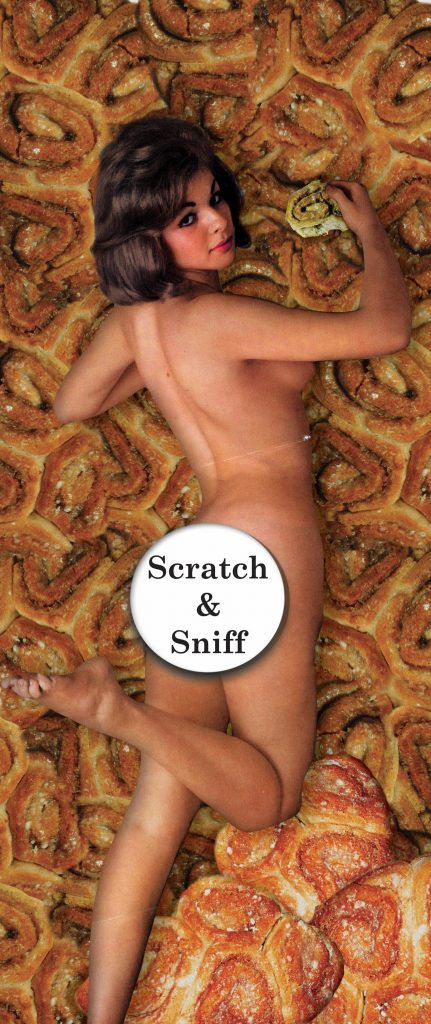

Seated casually around a table covered in brown butcher paper I survey the room and the individual across from me, international artist, Katherine Rhodes-Fields. We’re in Houston Community College’s Print Studio, Katherine’s home away from home. The space, is impressive- a large, fluorescent lit and heavily ventilated tile room. Glass palettes, drying racks, and corrosive cabinets culminate beautifully into a very modern printing house. As a former student of Katherine, the air for me is tinged with nostalgia. Katherine begins by discussing the lovingly named behemoth printing press to my left, Bertha. “Bertha she is a 3×5 ft Intaglio Press that was made by the Conrad Press Corporation, according to the 2012 catalog, she was worth $17,000 brand new. These days she would be anywhere between $20-23,000.” I stop to consider that information. A necessity for the art of printmaking – the press – and this one costs more than my car. This artist is on another level. “She’s a hefty piece of equipment, she’s a rare piece of equipment here in town because of her size. She’s a hallmark.” We move to the next set of presses, Glick Master Presses, a Griffin Electric Litho-press (now out of production), and a handmade press she inherited with the studio. Since Katherine uses a non-toxic intaglio process she converted the old intaglio room into a screen-printing space, complete with a pricey, vacuum-equipped contact exposure unit, another rarity. This studio has everything any printmaker could need, and probably a few things they didn’t know they needed. Katherine equates all of this to a simple statement, “It allows my curriculum to be really flexible.”  Katherine Rhodes-Fields “Billboard” SEEKING THE PATH OF THE ARTIST “When I was little, kindergarten, I would spend my summers with my grandmother in Vicksburg, Mississippi and she was an artist. While I stayed with her I learned how to draw, and to use watercolor, and to use pastels. I mean we had crayons and stuff like that, but I was constantly learning with these materials that a lot of people don’t have access to at that early age. My grandmother’s home was filled with artwork; my grandmother’s, her friends, and all the people she knew, so I had exposure there and in my own home. We had original paintings, drawings, and prints – things like that all over my home growing up. I knew about art, and also my family encouraged me to be an artist. There was never a moment when my family said, you’re never going to make money from it.” She explains to me that her grandfather was a photographer and a writer, she recalls he had a darkroom in the home, right beside her grandmother’s art studio. “It was always part of our family condition to be around this creative world. My mother was an English professor, so language and art have always been the core of my family.” I ask Katherine if she knew she wanted to make a career of art early on and she confirms she did, as early as 6th grade.  “I had a very impressionable experience in my art class, we had a local artist teaching. He was doing a lot of extraordinary things in the community – he was working with the school system and having murals painted by students, things like that. I got to do some incredible things, believe it or not, in a Mississippi public school.…I just had all these wonderful opportunities that were presented to me. I liked to explore lots of different things, and I found that I enjoyed art the best – that I felt natural towards. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.” Starting at such an early age, I wanted to know her time-frame, how long from choosing to become an artist to success? The answer – not very. In her high school sophomore year, Katherine won a local art competition with a water color of irises. After a brief showing at the public library, this would become her first sale. From there she studied at the University of the South (Sewanee) where she obtained a BA Cum Laude, in Studio Arts. She chuckles about the unique traditions of a small university, such as having a business dress code for fine arts students, while I sat mouth agape at the idea her small collegiate community – her graduating class had 300 students. Like many of her classmates, Katherine was encouraged to study abroad. She spent nine months studying Environmental Art at the Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, Scotland. This was during the dawn of installation art, and she was intrigued. “[At that time] Earthworks, or installation art as it’s called now, was never really introduced into the curriculum in the United States, but it was a new emphasis in Great Britain and Europe. I studied monumental or installation/environmental art at the Glasgow School of Art. A lot of my friends were going to Nashville or Atlanta, but I wasn’t interested in that. I graduated, bought a one-way ticket, acquired a work visa, and I moved back to Glasgow. I just loved being there, there was something about the spirit of that city.” HEARING THE MESSAGE Our conversation shifts to a discussion of Katherine’s work as a collective effort. I wanted her perception of the message her work(s) communicate and the process that gets her to that place of connection.  From Rhodes-Fields’ Woodblock Series “When I was in school in Glasgow learning about installation art, it really pushed the boundaries of what art was – and these days I think it’s really important too, because people are on their phones all the time, they’re watching television, watching movies – when you go into an art museum there’s not much that is very exciting about a painting in a gold frame with pictures of people you don’t recognize or know about, right? That’s because people don’t read anymore. It’s about something of the other – and as an artist we’re challenged to create experience but think about, a priori (based on reason alone), the experience before you actually experience it. It’s that intrinsic universality that you can’t really say, but you know it’s something that is within everybody. But the a priori gets reinforced by the empirical. So, what I’m exploring is different ways of asserting the a priori with my own experiences, but creating a more universality of experiences for my audience. The reason why I do that is because we as artists, I feel, in the contemporary sense, are losing our audiences – I think that we need to remember. When I make art, I want to think about not just the eyes, but the touch, the smell, the heat, the skin – you’re not supposed to touch art, but if you change the temperature in the gallery it still creates a visceral reaction from the body. I think about the body and the mind, that’s my process. How can I help my audience? It’s the quest for knowledge.” Katherine is well-read. She is very knowledgeable about chemistry as well as philosophy, literature, and the arts. The strides taken in her quest for knowledge are evident in the modifications, or leaps towards modernization she achieves in her work and in her classroom. I ask her how she came to the archaic craft of printmaking. “What brought me to Printmaking is that it really challenges an individual, whether you’re teaching or making art with it. Here was an artform that relies on all of this knowledge (learning chemistry, philosophy, art history) to move ideas and things forward. It also aligns with my thought process of how art should be democratized. Every person loves beauty, what beauty is undefinable. I like that challenge of creating an aesthetic moment. Now how I go about that – if it’s through uses of language and humor or if its through use of color – it is about having that moment. It’s about taking these larger philosophical ideas that do relate to aesthetics, and how we as humans respond to our quest for beauty and love and these larger things – and kind of pushing the boundaries around to create an experience that relates to gender or a region.” INSPIRATIONS “I am a woman and I have constantly [held] a conversation, in my work, about what it is to be a woman. To be the feminine and my experience being the feminine. Which is really kind of different from the experience of the feminine of other people from where I am from. I am making work that talks about the challenges, but as well as the accomplishments, and kind of juxtaposing them together about being of the female. I’m not trying to exclude the male experience from that, as a matter of fact I enjoy that, and have made work that brings it all together.” RELEVANCY LOST She voices concerns that some of these subtle efforts are lost on the contemporary audience, that the message is muddled or often misunderstood.  From Rhodes-Fields’ Plague Doctors Series “When I was in graduate school I did a series of works with the pomegranate fruit, this was actually a symbol of fertility, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, if you look at churches and synagogues you’ll see it. Then on the flip-side of that it also represents original sin -if you think about it the Garden of Eden, in the middle-east, apples don’t grow there, people. What looks like an apple, doesn’t taste like it, but looks like it, grows on a tree, and is red like an apple? – a pomegranate. There is also the myth of Persephone – this one thing, this object… that’s how I work, I think about all these things and what can I do to draw my audience in but also to inform them? I start with an object and push that object to speak for things, so in essence what it becomes is an extended metaphor – it is the conceit [the metaphysical conceit, associated with the Metaphysical poets of the 17th century, is a more intricate and intellectual device. It usually sets up an analogy between one entity’s spiritual qualities and an object in the physical world and sometimes controls the whole structure of the poem], that I am dealing with. I think as an artist, you are telling a story through images – it’s a visual language.” An image that has become synonymous with Katherine’s name is that of the Plague Doctor, it is a subject that has been dominate in her recent works. “The plague doctors represent ignorance. [The mask] didn’t really do its purpose of preventing disease from spreading. It represents that idea of humanity, no matter what technologies we have ultimately its futile to try to fight it …humans are mortal, I am human, therefore I am mortal.” “What we forget about is our own mortality, or we try to not face our own mortality so we create these circumstances to prevent that from happening – and unfortunately a lot of that is ignorance, not stupidity. I chose the plague doctor because of my background in history, I learned a lot about European History, about the plague – [plague doctors] they’re scary as hell, the thing is – we are all just so oblivious to it all. I started making plague doctors in 2005, in a painting. Then in August Katrina hit, and my family was affected – there was a span of time that I couldn’t hear from them. I had just moved, I didn’t even have a TV yet, I had to go to my neighbors houses to watch it [on the news], I didn’t have a house-phone and none of the cell phone towers were working, I mean it was bad – catastrophic. I noticed that people were wearing bandanas over their faces, people were wearing plastic bags for shoes – making do with what they had; but they were going around putting X’s on people’s houses, which is exactly what people did, what plague doctors did. That’s when I started making plague doctors with the X’s.” THE ROAD TO NOW/ CONTROVERSY  From Rhodes-Fields’ Woodblock Series Katherine shares the tale of an exhibition held in St. Louis, Missouri. She was teaching at Webster, and was taught a unique form of printmaking, Moku-hanga (a hand printing technique using water-based ink, absorbent Japanese paper, and a paste derived from rice) from a colleague. Her colleague conveyed the concepts of classism affecting this art form, because in certain cultures there is a type of racism regarding the consumption of rice – i.e. one country would not consume rice grown elsewhere. In consideration of her own heritage, and the classism/racism affecting her home she began to explore moku-hanga, with a unique twist. “It got me thinking about food-stuffs, and how racism and divides of cultures create this kind of schism. I was living in the mid-west and I am from the deep, deep south; and the perception of the deep south is that we are all racists, I mean I’m generalizing – please forgive me, but that has been my experience.” “I started thinking about food-stuffs that were uniquely connected, like the rice was to the culture, a reflection of that culture, and it’s very simple, for the American South, it’s fried chicken.” Selecting a recipe from a vintage cookbook, she fried up some civil-war era chicken and used the fats as a replacement for the Nori [rice] paste. Rather than use ink, she utilized charcoal, creating woodblock circles. When people learned about these modifications to the traditional process they began going up to the prints and sniffing – to see if they smell the fried chicken. “This was not archival, this was seriously experimental printmaking, but I was very excited because it was a way of being expressive in the act of making.” This exhibition led to the idea for the show Finger-Licking Good. “It got me thinking about the possibilities of using this thing that is not a traditional art material… I had a Playboy magazine [circa 1970, signed by the centerfold] and used a technique called, Chine-collé, and the chicken fat and I made Finger-Licking Good, which featured naked ladies that could be viewed through the transparency [of the chicken grease], and that created the idea of Scratch-N-Sniff. I took the older [Playboy images] ones, the pre-breast augmentation, naturally beautiful. I scanned all these centerfolds, and from there I altered the images. I took photographs of foods and inserted them as the backgrounds, removing the original backgrounds of these centerfolds. I chose them based on the colors, and the positioning of the bodies -of the parts that were recognizable, and I discretely changed their lipstick to make it look – I played with color theory, and then I affixed a digital Scratch-N-Sniff sticker, it was a white sticker that said Scratch-N-Sniff on top of their naughty-bits and it was relative to the food in the background. Because women as we know are comestibles; we are called cupcake, pudding-pie, our breasts are called melons, the term chick -does not mean chic, it means chicken, and a chicken is a young prostitute. Our butts are called buns, and they call our lower area fish, fish-tacos…if you think about it, and you know, honey or hon, sugar, pumpkin, peaches – women’s bodies are associated with things you eat and consume, and then literally, a centerfold is purchased for consuming.” Curious about how she created the scent for these images I ask her to divulge some of the process for this project. “These are not traditional prints, these were actually printed digitally onto plastic banners because I wanted them to be really big. These banners were six feet tall by three feet wide, so these women are life-size. It was a challenge because its vinyl, plastic vinyl – so I had to figure out a way. I went to stamping, I went to the craft-world and found a way to affix things to plastics and I created the scents using Kool-Aid, essential oils, seasonings. I melted them together and applied them to the plastic banners and then adhered them with a heating-gun, so they would apply but also you could still scratch them. I had this plastic that you could scratch, and it would release the scent.”  From Rhodes-Fields Scratch & Sniff series “I’m exploring again, in a bigger, broader scope that was a little bit more relevant to people in contemporary society. It was a huge success, an independent gallery in St. Louis exhibited them. There were photographs of little old ladies, little old men, young people, all kinds of people -scratching-n-sniffing and having a great time, laughing about it. They were laughing at themselves, and they were laughing at the fact that we can modify women in this way, we call women food-stuffs, but also we realize that when we walk up to this image, there are no breasts there –the woman is not there, and that what your scratching and smelling is not the food that is in the picture, it’s a made-up chemical scent for you to think about that food. It doesn’t really exist. Its about the synthetic experience, that we in our minds are placing that pubic region there. Its not there. Its not real. What I’m talking about is the experience of the real and when we bring our experiences to it. It was kind of magical in the response that people get. I’m really proud of that work, it was years in the making – the span of 3 years.” Katherine tells me she has no intention of selling the works, she wasn’t thinking about a collector or a gallery showing the work. This was about the process, about the conversation. She’s never sold one, in honor of the original copy right held by Playboy. The work wasn’t without controversy thought. In 2009/10, while working as a visiting assistant professor at the University of St. Louis, Katherine was asked to show the work at a different location. Reluctant at first, she agreed to a one night show, with signs up to warn people of the nudity. She would also make a small piece to auction it off, with proceeds going to kids programs run by the Arts Council. The controversy started when the local paper wanted to do a feature. “I gave them my artist’s statement, and this is a lesson to be learned…artist statements aren’t really meant to be printed in a newspaper. Unfortunately, my artist statement was printed verbatim, which I’m actually fine with… but the editor decided to put the promotional image, in full-color and then above it said Nude Art Show. That went to print without me reviewing. I had been teaching class all day, and I got a call from the director of Arts Council and he said we have a huge problem – have you seen the paper? I leave and get a copy of it, and I am just sick. Not only that, but people who read the paper called the mayor’s office, and the mayor called the director of the Arts Council and threatened to take away all of the city funding for the Arts Council if they followed through with the show.” I clarify with Katherine that they weren’t actually nudes, due to the placement of the Scratch-N-Sniff stickers. “Thank you, that was the kicker. That was the clencher – and even if they are nudes… I mean have you been to an art museum lately?” Katherine explains that a private gallery then stepped in and offered to have the show at the private location – in a tent – where the work was hidden from casual gaze. For the original gallery she made a new series, called Safe-Prints, which were actually images of safes Chine-colléd to larger substrates. “They were hung like Scratch-N-Sniff was supposed to be and it was the Safe Art. That was my response, you want safe art – fine here’s safe art. Playing with the language.” “We have the Scratch-N-Sniff show, and it did not go over well, not at all. The people that came were like, this is awesome but the [overall] conversation was not about what I was saying with my art, the larger conversation about why are women consumables? Why do you feel ok doing this? Do you realize that it’s not real? the idea of real versus perception, that your imagination is stronger than the actual. That conversation never happened, publicly. The conversation had shifted to censorship. Following that one night only show, the representatives of the county met, and they withdrew the funding from the Arts Council.” I ask her if she felt the situation was utilized as a scapegoat to pull the funding, that funding for these types of councils nationwide have come under attack. “I was an opportunity, I feel. What happened was that on social-media, and the media in this town and state I was in – I believe a council member called me trash… not the art, trash, but me, I was called trash – he called me trash. So, it changed, you can call my art trash all you want, but don’t call me trash. There were Facebook hate-pages created about me, not my art, me as a person, as an individual. There were people that wrote letters to the University, to the Art Council. I couldn’t go to the grocery store without people coming up to me and calling me names. It was tough. It shifted a lot of things for me. People wanted to interview me, I refused. The art speaks for itself and remember I’m not my art, I just make it. It’s a conversation I’m trying to create, if you’re interested in talking about. Read my artist statement – it’s on my website – make a decision on your own. It became this horrible, and I call it horrible, because for me it was the most horrific thing that could happen: I was being called something that I’m not, and the funding was being taken away from an organization that did such great things, that I believed in, that I supported. It was really unfair.” The exhibition was in September 2011, and I in March of 2012 Katherine found out her contract with the University would not be renewed. Does she think the show was a factor? “Whether or not Scratch-N-Sniff was the sole reason for it, I don’t know. I was never given a reason because I was a visiting-professor, legally the university didn’t have to tell me anything. So, I don’t know, I’ve been told different stories, different things and I believe them all. At the end of the day I had to leave, and it was tough.” I ask Katherine if she feels that the situation followed her to Houston. “I’m here now, and that controversy hasn’t followed me here. It has followed me personally, but it did not have a negative impact on my career going forward. I teach here [Houston Community College] and I’ve taught at University of Houston Clearlake. I have had shows here. I have a show coming up in Macedonia, at the National Museum of Arts in Tetovo. I believe that controversial art is important. I think that it did impact me personally in my art-making, I mean I’m not changing so much, I’m still building on the same things I always have, just in a different way. For me, selling art – if someone wants to own some of my work, that’s great, and I’m happy. I make editions to exhibit and show, but I make art because I have to. It’s just who I am, I have to make art in order to survive. That’s how I process my thoughts, it’s just the manifestation of my thought process. I would just kind of burn out and die if I didn’t make art anymore.”

|

|

Miranda Ramirez, who interviewed Katherine Rhodes-Fields for this piece, is a writer of both fiction and creative non-fiction, who seeks to marry literature with visual artistry. As a journalist she seeks to open a window into the unique and pulsating beast that is the Houston Arts scene. You may find her previous publication in Glass Mountain, Vol. 20. |

|

Empathic Empiricalist | an Interview with Katherine Rhodes-Fields

by Miranda Ramirez

Issue 03